The new paradigm of sustainable development

Pieter Lammers with his family in 2019

Pieter Lammers was development cooperation policy officer in the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs at the time Both ENDS was founded. He has been one of those people that was crucial for the development of Both ENDS during ‘the early years’, as he supported our view on equal partnerships with Southern actors and on the importance of sustainability. For Both ENDS’s anniversary, he looks back on the context of development cooperation in those early years.

‘At that time environment was not at all an issue in the development conversation,’ explains Lammers. ‘There was a very small unit on energy, with two of us, but not much happened for the first couple of years. The Ministry was not really interested in environmental issues. There was one ecologist in the whole Ministry.’

Environment and development

Yet awareness was growing. Lammers describes two emerging trends, both of which were critical to the founding of Both ENDS and ultimately reshaped the field: increased recognition of the need for sustainable development and the autonomous power of Southern civil society. In October of 1987, the UN published Our Common Future, also known as the Brundtland Report, which helped introduce environmental issues into the global development agenda. From Lammers’s vantage point, the parliamentary election of 1989 and the appointment of Jan Pronk as Minister for Development Co-operation marked the turning point. Pronk proclaimed sustainable development a top priority, and gave Lammers and his environmentally-minded colleagues a key role in developing Ministry policy. Lammers was responsible for writing the sustainable development chapter of the Ministry’s new policy paper, where he brought the economic, social and environmental issues together into one conceptual framework.

The policy paper, Een Wereld van Verschil (A World of Difference), was finalised in 1990. ‘The Minister wanted to stress that things were going to be very, very different,’ says Lammers. At the global level, the Netherlands and a handful of other countries played a major role in pushing forward the sustainable development and climate agenda. ‘We had very good cooperation with the Ministry of Environment,’ says Lammers. ‘Fritz Schlingeman, Joke Waller [who later left her legacy to Both ENDS to found the JWH initiative, ed.] and a few other people – we closely cooperated in bringing the sustainable development agenda forward.’

The new policy led to a reorganisation of the Ministry and the creation of a new – and very well-funded – programme on environment and development. With palpable delight, Lammers recalls: ‘We went from being a very small unit with nearly nothing to being a very large organisation with lots of resources.’ It was during these same years that IUCN staff came to the Ministry with a proposal for Both ENDS, which was first funded by the Ministry as an IUCN project and subsequently as an independent organisation.

Strong civil society

Alongside the new focus on sustainable development was a shift in understanding about the role of civil society in the South. ‘There was a growing understanding that there could be no sustainable development, there could be no development at all, if you don’t have a strong civil society. There was a growing realisation that the classical, top-down model of development aid was not really the way to work together,’ Lammers explains. ‘NGOs in the South really came into the picture – not as before, not as ‘implementers’ of Dutch development aid policy – but as independent, autonomous NGOs. You need equality and a certain amount of reciprocity in order to be sustainable and effective. That’s where Both ENDS came in. The name says it: linking organisations in North and South that are working on the same issues and see how they can help each other.’

Sustainability agreements: reciprocity, equality and participation

Lammers played a leading role, along with Both ENDS and many others, in a groundbreaking initiative that tied together the new approaches to development and Southern civil society. Following the landmark UN Conference on Environment and Development in Rio in 1992, more than 175 countries signed on to the Rio Declaration, which laid out the principles and path for sustainable development. Lammers and colleagues in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Environment were eager to put the Declaration in practice: ‘We wanted to find a way and a scale to make the Rio Declaration work.’ With the backing of both Ministers, an innovative cooperative process to develop reciprocal, sustainable agreements was launched. The process involved the Netherlands and three similarly small and environmentally-committed countries in each region of the South: Costa Rica, Benin and Bhutan.

‘The principles of the relationship were reciprocity, equality and participation. The participation part was very important. That’s where Both ENDS played a major role.’ The initiative began by inverting the traditional North to South approach to development aid: a Bhutanese delegation visited the Netherlands to reflect and comment on sustainability issues in the Netherlands. More exchanges followed, with Both ENDS playing a key role in ensuring participation by a wide range of civil society actors in the participating countries. The idea was to bring together a variety of people and perspectives, including government representatives, NGOs, labour unions, police, commercial organisations.

‘The approach was a complete departure from the classical development paradigm, which essentially promoted replication of the Netherlands’ historical path to development’, explains Lammers. The sustainable development paradigm, which defined the collaboration, was built on the understanding that the Netherlands, no less than Costa Rica, Benin and Bhutan, had to follow its own unique path in order to reach a common place of sustainable development. ‘The Netherlands is extremely ecologically unsustainable, while Bhutan is one of the only countries in the world that absorbs more carbon than it emits. You can’t copy each other, which means you needs a lot of dialogue and discussion. And that’s what we did.’

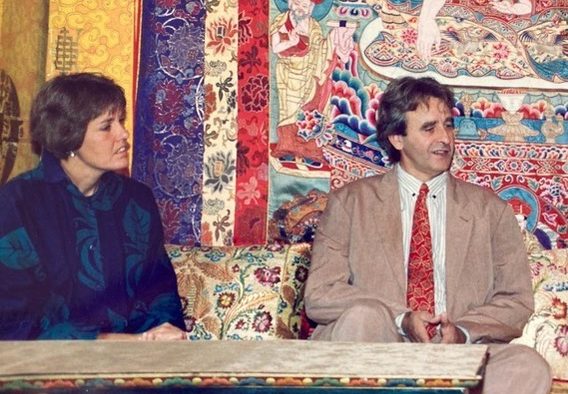

Pieter Lammers with his colleague Chris Enthoven, the Bhutan coordinator at Ecooperation, the agency responsible for the Sustainability Agreements. They are visiting the king of Bhutan, who has been cut off the picture because it’s inapproriate to spread his image. Bhutan, 1994. Photo: Pieter Lammers

Women on their way to a festival, Bhutan, date unknown. Photo: Pieter Lammers

Lammers describes Both ENDS as ‘instrumental in forging bonds with organisations’ in the countries involved. Both ENDS took part in all the visits and a staff person was assigned as a contact in each of the countries. ‘Twenty years later I still meet people in Bhutan who talk about how much the sustainable development agreements meant to them and to their organisations. It was an exciting time,’ states Lammers. Ultimately, the political winds shifted and when the agreements were formalised into treaties, complications arose. Decision-making was shifted to the embassies and, in Lammers’s analysis, created a heavy layer of bureaucracy that had not previously existed. ‘Instead of being a description of our relationship, it became a prescription. It became so solidified and we needed to keep things fluid.’

Southern civil society should play an independent role

Both ENDS’s approach – based on equality and respect for partners’ autonomy and expertise – was unique at the time. Most Dutch development aid was channelled through a handful of Dutch organisations with offices in Southern countries. In 2001, Lammers authored another influential report, ‘Civil Society and Structural Poverty Reduction’ which emphasised the importance of equality and independence of civil society organisations in the South. ‘The idea was that if you want civil society in, for example, Africa, to play their independent role, just like civil society in the Netherlands does, then they should be independent and equal partners to Dutch development organisations and the Dutch government. They should be able to pursue their own agendas.’ The report’s conclusions, which were strongly supported by Both ENDS, further articulated the new vision for international cooperation. Soon after, in 2004, Lammers left the Ministry. He was disappointed that the report’s recommendations weren’t taken up by the time he departed. ‘Everyone agreed, but nothing happened,’ he says with a chuckle.

Fortunately, the story does not end there. In 2015 all United Nations Member States adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, ‘the shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future’. Sustainability and development are solidly fused together. Likewise, the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs now invests significant resources in strengthening the lobbying and advocacy capacity of civil society in the South. Its current funding framework places particular emphasis on local ownership and equality in relationships between organisations in North and South. Both ENDS participates in two consortia, the Fair, Green and Global Alliance (FGG) and the Global Alliance for Green and Gender Action (GAGGA) respectively, which were selected by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs as strategic partners for the coming five years. Where Both ENDS is the leading organisation in the FGG Alliance, GAGGA is being led by a southern organisation, the Fondo Centroamericano de Mujeres (FCAM, Central-American Women’s Fund), based in Nicaragua.

Pieter Lammers can only appreciate this shift of power. “Civil Society Organisations anywhere should be able to act independently and autonomously from governments, and relationships between CSO’s in North and South should become ever more horizontal, equal and reciprocal. Both ENDS is an important actor in this development.”

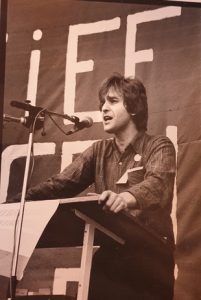

Pieter Lammers speeching at a Milieudefensie protest, between 1975-1980

About Pieter Lammers

Pieter Lammers began his career in international development cooperation at the FAO in Rome, where he worked in the early 1970s in lieu of military service. When he returned to the Netherlands in 1975, he worked on energy issues at Milieudefensie. In the 1980s he worked as campaign manager on acid rain for Friends of the Earth International and staffed its International Secretariat. In his spare time, Lammers was active in the movement against nuclear power. In 1987 Lammers became a development cooperation policy officer in the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, a position he held during the founding of Both ENDS. He left the Ministry in 2004 to become an independent consultant and later a tour guide in Bhutan and other Asian countries.